使用MTU设置优化Ubuntu Internet速度

https://appuals.com/how-to-optimize-ubuntu-internet-speed-with-mtu-settings/

While computer texts differ in their application of the term, Ubuntu uses the TCP Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) to refer to the largest size a TCP packet a machine can pass over a TCP/IP networking connection. While calculating this value is relatively simple and defaults work on a majority of machines, it might be possible to further optimize your system if packets are fragmenting because of unusual settings. Sending large single outgoing packets is more efficient than sending multiple smaller outgoing ones.

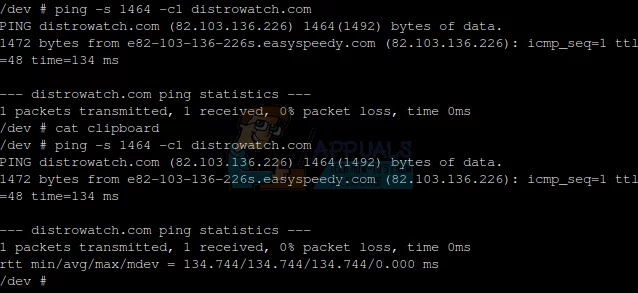

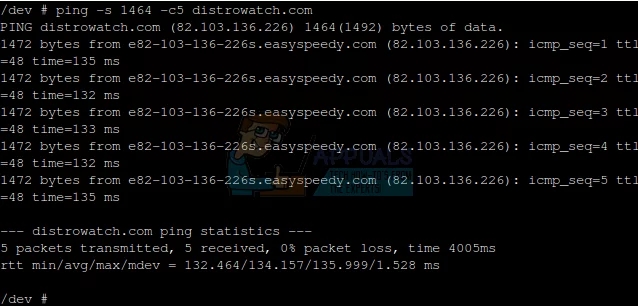

The easiest way to find out the correct MTU value for your machine is to open up a terminal window. Hold down CTRL, ATL and T or perhaps start it from the Unity dash. If you’re working with Ubuntu Server, then you’ll default to a CLI interface with no graphical environment at all. Once you’re at the terminal, type in ping -s 1464 -c1 distrowatch.com and wait for the output. If you’re not receiving anything, then your networking connection hasn’t been configured correctly. Assuming you received proper output, then look for a section that reads 1464(1492) bytes of data, which indicates you’re sending the packet with 28 bytes of header information.

Method 1: Examining ping Output for Packet Fragmentation

The ping command will let you know if the packet was sent as more than one fragment with multiple header data attached. Examine the output for any line that warns about something regarding “Frag needed and DF set (mtu = 1492)” or any similar text. Depending on which version of ping was included with your version of Ubuntu, the warning may be worded differently. Should this text not be present, then more than likely you’re already working with some MTU measurement that isn’t sending out fragmented packets at the present time.

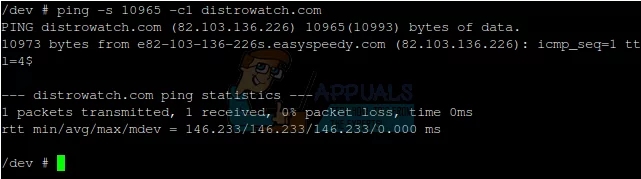

To find the most optimized MTU for your system, you would want to run this ping command with a small packet size, and then over time increase it until it begins fragmenting after which you consider this your cutoff point. Keep in mind that MTU = payload + 28, since there needs to be some room for the header data. Now, if you can increase the size to something very large without any fragments, then your network interface might be able to handle massive packets without the need for generating fragments. When you finally do see a Frag needed warning, this means that any packet sent with a payload the size you ran or higher will send as multiple packets. Assume that if you try ping -s 2464 -c1 distrowatch.com without any warning, but ping -s 2465 -c1 distrowatch.com sends a warning, this means that 2,464+28 is the largest MTU setting your TCP/IP configuration can handle before sending multiple fragmented packets. It might take a few moments to pinpoint an exact value.

Once you have a value in mind from running the ping command multiple times, you’ll need to run sudo ifconfig to find a list of known network interfaces. Ubuntu and its derivatives hash out the root account, but we operated from a shell created by sudo bash for our examples. It’s recommended you rather just preface each command with sudo individually.

As soon as you know the correct device, try:

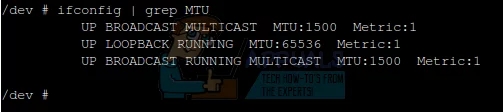

sudo ifconfig interfaceName mtu ####

Replace interfaceName with the name of the network adapter you’re working with, and then replace #### with the size you found plus 28 for header information. You can run ifconfig to see what the default MTU was for your NIC and run it again multiple times to see if this previous command changes it. Some network interface adapters simply won’t let you change it. If that’s the case, then further optimization will be fruitless unfortunately. If, however, this worked, then you can actually make it permanent. Try running ifconfig | grep MTU to find all the values if you have multiple connectors, and then you can then match the values to the connectors you’re working with.

Method 2: Making MTU Optimizations Stick

So far you’ve made no permanent change to your system. If you reboot, then you’ll wipe any changes out, which is good if you’ve made some sort of mistake and find that you can’t connect to the Internet any longer. On the other hand, if you’ve found an accurate value for your MTU, then you’ll need to edit the ![]() document. This is probably a good time to make a copy of it in case something happens. Try

document. This is probably a good time to make a copy of it in case something happens. Try ![]() or something similiar so you have a copy just in case. If you’d like to edit it graphically, then type

or something similiar so you have a copy just in case. If you’d like to edit it graphically, then type ![]() and enter your password. If you’re using Kubuntu, Xubuntu or Lubuntu, then you’ll need to replace gedit with the graphical text editor your Ubuntu respin uses. Xubuntu, for instance, uses mousepad instead of gedit. If you’re using Ubuntu Server or simply prefer working with the command line, then instead type

and enter your password. If you’re using Kubuntu, Xubuntu or Lubuntu, then you’ll need to replace gedit with the graphical text editor your Ubuntu respin uses. Xubuntu, for instance, uses mousepad instead of gedit. If you’re using Ubuntu Server or simply prefer working with the command line, then instead type ![]() , assuming you’re not using a root shell.

, assuming you’re not using a root shell.

Irrespective of which method you used to edit it, find the name of the interface ifconfig spit out before. Let’s assume you were looking at the first Wifi connector on your machine, which would probably be named wlan0 or something similar. In this case, find a snippet of code that starts with iface wlan0 inet static or something similar. Your mileage may vary, but the next line will read address followed by an IP address in ###.###.#.## format. It might be formatted differently if you’re on a native IPv6 connection. You’ll have a netmask and gateway line, followed by something that lists a host name or something similar. At the bottom, you’ll have another line that reads mtu and a number. Replace that number with the optimize MTU value, save the document and then exit the text editor. You’ll want to reboot the system to ensure it worked.

Should everything be fine after several reboots, then delete the interfaces.bak file in your ~/Documents directory. You could instead use sudo mv ![]() and then

and then

![]() if anything went awry in the process.

if anything went awry in the process.

Method 3: Editing TCP Receive Window (RWIN) Settings

Ubuntu refers to the largest amount of data that a host accepts before it acknowledges the sender as the RWIN value. If you download a 30 MB file, then the remote server doesn’t actually immediately send you a 30 MB block of data. Your Ubuntu host sends a specific RWIN number when it requests the file, and then the server begins streaming data until it’s reached the number of bytes before it waits for an acknowledgement that your system got the data. Once the server receives this, it begins to send additional blocks before waiting for another acknowledgement.

Latency is the time it takes to transmit and receive packets from a remote server. Connection rates contribute to this value, but so do numerous other delays. The ping command will explain latency in terms of round-trip time (RTT) numbers. Look at the output from our previous ping of DistroWatch. You’ll find a line that reads time=134 ms, which is how long it took for packets to go round trip from our Ubuntu machine to distrowatch.com and back again. We were sending a 1,492-byte packet, so at 134 ms we could calculate a formula to find the total transfer speed:

1,492/.134 seconds = 11,134.328 bytes/second, which comes out to approximately 10.88 binary kilobytes per second. That’s rather slow overall, which is why RWIN is in place to keep you from having to acknowledge each packet sent individually.

RWIN settings in Ubuntu are separate from MTU settings. Calculate the Bandwidth Delay Product (BDP) for your Internet connection with this formula:

(Total maximum bandwidth your Internet connection should supply in Bytes per Second)(RTT in Seconds) = BDP

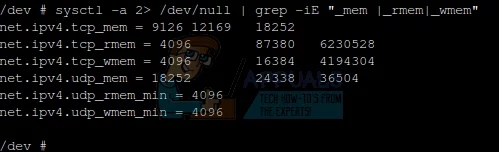

TCP packet size doesn’t influence RWIN, but the packet size itself is influenced by the value selected in Method 1. Use this command to find the kernel variables related to RWIN:

Please keep in mind there is a space after _mem, but nowhere else in the quoted text. You’ll get several values back. The ones needed are net.ipv4.tcp_rmem, net.ipv4.tcp_wmem and net.ipv4.tcp_mem. The numbers after these values represent the minimum, default and maximum values for each. They represent the receive window memory vector, send vector and TCP stack vector. If you’re running Ubuntu Kylin, then you might have a long list of additional ones. You can safely ignore any of these additional values. Some users of Kylin might also see some of the values delineated in other scripts, but once more simply look for these lines.

Ubuntu doesn’t have an RWIN variable, but net.ipv4.tcp_rmem is close. These variables control memory usage and not just the TCP size. They include memory eaten up by data socket structures and short packets in massive buffers. If you want to optimize these values, then send the maximum size packets you set in Method 1 to another remote server. Let’s use the 1,492-byte default again, subtracting 28 bytes for header information, but remember that you may have a different value. Use the command ping -s 1464 -c5 distrowatch.com to get additional RTT data.

You’ll want to run this test more than once at different times of the day and night. Try pinging some other remote servers as well to see how much RTT varies. Since we had an average of slightly over 130 ms each time we tried it, we can use the formula to figure out our BDP. Let’s assume you’re on a very generic 6 Mbits/second connection. The BDP would be:

(6,000,000 bits/sec)(.133 sec)*(1 byte/8 bits) = 99,750 bytes

This means the default net.ipv4.tcp_rmem value should be somewhere around 100,000. You could set it even higher if you fear that you’d get an RTT as bad as half a second. All values found in net.ipv4.tcp_rmem and net.ipv4.tcp_wmem need to be set identically, since transmission and reception of packets happen over the same Internet connection. You’ll generally want to set net.ipv4.tcp_mem to the same value used by net.ipv4.tcp_wmem and net.ipv4.tcp_rmem since this first variable is the total largest buffer memory size set for TCP transactions.

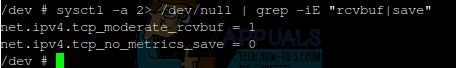

Issue the command ![]() and see if both of these settings are set to 0 or 1, which indicate a state of off or on.

and see if both of these settings are set to 0 or 1, which indicate a state of off or on.

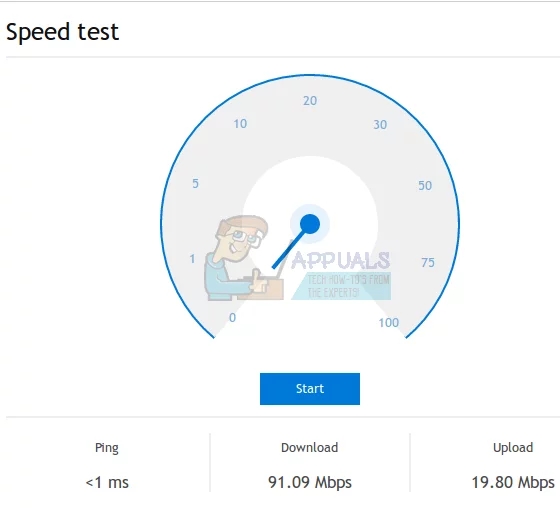

Setting net.ipv4.tcp_no_metrics_save to 1 will force the Linux kernel to optimize the receive window between the net.ipv4.tcp_rmem and net.ipv4.tcp_wmem values in a dynamic fashion. When net.ipv4.tcp_moderate_rcvbuf is enabled, it prevents congestion from influencing subsequent connectivity. Before making any permanent changes, conduct a speed check through http://www.speedtest.net or http://www.bing.com/search?q=speed+test to make sure you have a handle on your measurements.

Temporarily change the variables with your calculated values. Make sure to replace the #s with your calculated sums.

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.tcp_rmem=”#### ##### ######” net.ipv4.tcp_wmem=”#### ##### ######” net.ipv4.tcp_mem=”#### ##### ######” net.ipv4.tcp_no_metrics_save=1 net.ipv4.tcp_moderate_rcvbuf=1

Retest your connect to see if the speed has improved, and if not tweak your command again and rerun it. Remember that you can push the up key in your terminal to repeat the last used command. Once you’ve found the appropriate values, open ![]() with the gksu or sudo text editor command from Method 1, and edit the lines to read as following, once more replacing the #s with your calculated values. You’ll of course want to also backup the

with the gksu or sudo text editor command from Method 1, and edit the lines to read as following, once more replacing the #s with your calculated values. You’ll of course want to also backup the ![]() file the same way you did in part one just in case you make a mistake. If you’ve made one, then you can also restore in the same fashion as well.

file the same way you did in part one just in case you make a mistake. If you’ve made one, then you can also restore in the same fashion as well.

net.ipv4.tcp_rmem=#### ##### ######

net.ipv4.tcp_wmem=#### ##### ######

net.ipv4.tcp_mem=#### ##### ######

net.ipv4.tcp_no_metrics_save=1

net.ipv4.tcp_moderate_rcvbuf=1

Save it once you’re sure everything is okay. Issue the following command:

sudo sysctl -p

This will force the Linux kernel to reload the settings in ![]() , and if all went well then it should give you at least a somewhat speedier network connection. Depending on your original defaults, the difference might actually be dramatic or potentially not noticeable at all.

, and if all went well then it should give you at least a somewhat speedier network connection. Depending on your original defaults, the difference might actually be dramatic or potentially not noticeable at all.

最后更新于